Here in Vermont, as in other places where crunchy Americans congregate, the 14th Dalai Lama is a popular guy. Folks like Cath and me who shop at community food co-ops and farmers’ markets—and are often vegetarian—tend to think of him as a wise and compassionate teacher.

Here in Vermont, as in other places where crunchy Americans congregate, the 14th Dalai Lama is a popular guy. Folks like Cath and me who shop at community food co-ops and farmers’ markets—and are often vegetarian—tend to think of him as a wise and compassionate teacher.

For many, it comes as a shock to learn that he eats meat. I know it did for me.

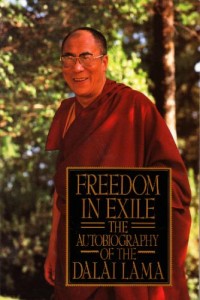

By the time I read about it in his autobiography, I had already abandoned vegetarianism, and his story resonated.

Back in the 1960s, he had witnessed the slaughter of a chicken and had sworn off flesh foods. Before long, though, his health began to suffer, with complications caused by hepatitis. Following his physicians’ instructions, he reluctantly returned to eating meat and regained his health.

What resonated even more was his commentary on Tibetans’ relationship with meat.

He notes that, in the 1960s at least, very few Tibetan dishes were vegetarian. Alongside tsampa—a kind of barley bread—meat was a staple of the local diet.

This, however, was complicated by religion. Buddhism, the Dalai Lama writes, doesn’t prohibit meat-eating “but it does say that animals should not be killed for food.” And there lay the crux of what he calls Tibetans’ “rather curious attitude” toward meat.

Tibetan Buddhists could buy meat, but they couldn’t order it, “since that might lead to an animal being killed” for them specifically. (This reminds me of a friend’s experience with a rabbit earlier this year.)

What, then, were Tibetan Buddhists to do? How could they eat meat without being involved in butchery? How could they consume flesh, yet prevent themselves from being implicated in killing?

Easy. They let non-Buddhists do it, often local Muslims.

These moral gymnastics might strike us as odd. But is the average American so different? Here, people’s distaste for butchery may be guided less by scripture than by squeamishness, the task assigned less by religion than by profession. The end result, though, is much the same. The dirty work gets done by others.

And there lies the crux of my own curious attitude toward meat. I prefer to take my own karmic lumps.

© 2010 Tovar Cerulli

A very interesting post, and one that highlights the difference between religious ethics and other ethics. In particular, mainstream American ethos is rooted in libertarianism and evangelical (from puritanical protestantism) Christianity. The first puts a priority on negative rights, the on universalism and dogmatic adherence. We Americans tend to meld these two, and believe that all people who have an ethos should behave as if their ethos applies to everybody else.

Your statement that they are “moral gymnastics” doesn’t completely hold true when viewed from another ethical perspective. The Buddhists in Tibet are held by one set of laws which are clearly stated, and they understand the local Muslims to be held by another set of laws. They do not think it appropriate to extend their laws to others – they do not necessarily believe that others are to be compelled to follow their laws, even if it means that the others won’t reach Nirvana so quickly.

The same is true for other religious perspectives, even some Christian ones. For example, I’ve known more than a few Mennonites who take the bus.

I hold an ethos similar to yours, in that I think that a person should take on some responsibility for their meat (I also think that vegetarians should take on some responsibility for their veggies, and kill rodents). But, I don’t know if the Tibetan Buddhists think they are committing moral gymnastics. I don’t know if the Mennonites are, either, though I think they are Calvinists, so the bus driver is probably screwed, anyway.

Your points are well made and well taken, Josh.

Yet, from my reading of the Dalai Lama’s words (“rather curious attitude”), I gather that he also sees something odd here, maybe even something humorous or gymnastic. He makes that particular point of mentioning that Tibetan Buddhists can buy meat, but can’t order it. Quite apart from the question of imposing Buddhist laws on others, I think he — perhaps like some other Tibetan Buddhists — sees the irony here.

Moral gymnastics. Ethical contortion. Don’t we all do that, some of us daily, to justify one thing or the other? Why would the Tibetan Buddhists be any different?

The story reminds me of one we discussed years ago in an anthropology and sociology seminar. Today, the details are vague, but I believe it was a sect of Buddhists (or was it Hindu?) who were forbidden to kill for food. Yet they often fished for their dinner. When challenged on this apparent contradiction, they argued that they did not kill the fish. They merely brought them out of the water, and then the fish died on their own.

Is it a stretch? Yeah, like wrapping your own legs around your head.

It’s funny how it works, but the more restrictive our set of rules, the more creative we become at finding ways around them… and at justifying those little evasions. To me, that’s a pretty good way to identify the artifice in an ethical or moral code.

Now to apply the same measure to hunting ideals, such as fair chase.

Oh, indeed we do. I agree: moral gymnastics don’t make Tibetans, Buddhists, or American grocery store shoppers unique or even bizarre.

And my own “curious attitude” — which, in great part, led me to hunting — is probably at least as strange.

I don’t know exactly how the Dalai Lama made his peace with his reluctant-but-necessary return to meat, with the need to flex his moral code.

I dunno, Tovar, but what strikes me about the Dalai Lama and Ghandi (whom you invoked in a previous post) is that while they’re so often seen as idealists, I find them to be immanently pragmatic individuals.

I know more about Ghandi than I do the Dalai Lama, but I can’t claim to have studied either of them to any extent. Nevertheless, I feel their messages because I think they reach out from a position based in reality. For example, we try to be as close to perfect as we can, knowing that we can never be perfect… and knowing as well that sometimes our idea of perfection is imperfect itself. The willingness to redefine perfection (those moral gymnastics) is probably what sets spiritual leaders like the Dalai Lama apart from others such as fundamentalist Baptists or “radical” muslims who would preach strict adherence no matter what.

The decision to eat meat despite holy teachings strikes me as an anthropocentric choice. Both of your examples made the choice to go against the teachings because they decided to value themselves over the creatures that are reduced to food. The concept of equal worth of all beings is a noble enough ideal, but the reality is that there is no equality. To sicken and even die for the sake of not harming animals simply tilts the balance in the favor of the animal… and that’s not equality either, is it? And what is our value to the universe if we willingly reject the sustenance it provides?

In Gandhi’s case, he only tried meat briefly in his youth and never went back to it, but he did abandon veganism for health reasons (adding milk back into his diet), just as the Dalai Lama returned to eating meat for health reasons.

I guess we could call them both “pragmatic idealists” — a very fine, mature, balanced kind of role model, in my opinion.

I wonder: Would the Dalai Lama “order” meat, thus causing a specific death, or perhaps even kill the animal himself? I wouldn’t be surprised if the answer is yes. I think he clearly sees the silliness inherent in making a distinction between those acts and eating an animal that’s already dead.

Sorry it’s taken me so long to dive in – crazy day. But I’ve been thinking about it and I think that all humans are prone to doing moral gymnastics over their food.

The vegans convince themselves that it’s OK to kill plants, but not animals.

The pescatarians convince themselves it’s OK to kill fish, but not animals of the land and air.

The grocery-store meat eaters convince themselves they’re not killing animals because someone else does it for them.

We hunters convince ourselves it’s ok to kill the animals *we* target, but it wouldn’t be OK to kill a neighbor’s dog, or for our neighbors to kill our cats.

And when we meet someone who seems to be troubled not a whit about killing, we say there’s something wrong with that person – that we should all have qualms when we pull the trigger – even though that’s probably the only one among us NOT doing moral gymnastics.

Some days I’d just rather be a lion and not give a shit. But most the time I think I really enjoy being this ridiculously complicated. Go figure.

Interesting, Holly. I’ll have to chew on all that.

On behalf of the vegetarian view, I think there is a strong case to be made — as in the religious tradition of Jainism — that plants are quite different from animals (Buhner’s writing and related research notwithstanding). For vegetarians, I think the central gymnastics are more tied to the fact that agriculture harms both wildlife habitat and individual animals, as Josh alluded to above. For years, as a vegan, I simply did not know or realize this, so I didn’t have to do gymnastics at all.

But are you aware of the moral gymnastics you do now? Or would you kill and eat your neighbor’s dog for dinner in the course of a normal week (not for survival in extreme conditions)?

I’m not convinced hunters’ moral gymnastics are the same as the ones you wrote of here. Distinguishing between what it’s OK to kill and what’s not isn’t exactly the same thing as deciding under what circumstances your food can involve death. But we do have our own funny little sets of rules that some outsiders might find just as amusing as the Tibetans’ meat rationale is to us.

I think humans always make in-group/out-group distinctions — this person is family, that person is a stranger, this dog is family (or a neighbor’s family), that deer is food — and treat other beings accordingly. Those distinctions vary culturally, of course.

I agree: what I wrote about here (how Tibetan Buddhists and American grocery store shoppers avoid feeling implicated in killing the animals they eat) is different from making distinctions among the species of animals, or individual animals, one will or won’t kill for food. I’ll kill a wild hare, for instance, but not a neighbor’s pet bunny.

I’ve been milking a goat recently who has the personality of my dog, only she is much smarter. Now I don’t know that I can eat lamb. Could I eat my dog? I never knew eating meat would be so confusing as I became close to the source of it…

I have decided not to raise meat rabbits becuase I can’t bear the thought of them living their lives in those tiny cages. Today a very sweet friend said “well at least they have short lives.” When I asked if that mattered to the rabbit she really paused.

It’s amazing how removed even the most considerate of us are from our food.

Knowing that the dalai lama eats meat makes me feel better about it but I agree that each bite of meat you take should give you pause for thought.

Today we slaughtered another pig and we will try and use every bit of it in homage, right down to lard for soap. It’s the least we can do.

Thanks for your thoughts, Annette. It’s true: the closer we look at our fellow creatures and the more we allow ourselves to connect to them, the more “confusing” meat-eating can be. For me, the confinement of animals in tiny cages is a lot harder to contemplate than killing.

Thanks, too, for your mindful treatment of the pig and other animals. As you say, it’s the least we can do.

Honestly, I truly believe that sometimes we think too much. I think all of us who eat meat do it in different ways and for different reasons. We buy it at the store, because it helps us stay away from the actual killing, or we actively pursue and kill it during the hunt.

Whatever way we spin it, though, we still eat the meat – whether we actively participate in the killing or not. Some of us are comfortable with it, some of us are not.

And we’re all human, so we’re going to – whatever the reasoning is why we actively or passively participate in the killing – spin it in such a way that helps us to sleep at night.

I actively participate, and I sleep just fine:)

Hey, Arthur. I don’t know what to think about you thinking that we think too much. 😉

You may be right. Maybe a lot us do what we do — whether that’s buying plastic-wrapped packages or killing deer — so we can sleep better. This is a very loose analogy, but it reminds me of what I’ve heard fellow volunteer firefighters say: most people run away from burning buildings, some run toward them.

I’m gonna go out on a limb here and say that “moral gymnastics” are most often invoked to circumvent ethical precepts that have, as their epistomology, religion.

Orthodox Jews aren’t allowed to do all kinds of things on the Sabbath, so they have things like elevators that stop on every floor, and appliances that automatically go off and on.

If you haven’t decided, for yourself, that something is wrong, and figured out why it is wrong, you’re in the position of following the letter of someone else’s (sometimes arbitrary) law. If you believe something to be wrong for clear reasons of your own, I think you’re much less likely to go the “moral gymnastics” route.

Holly, we treat animals differently from plants, and some animals (like invertebrates) differently from others because we’re responding to the degree to which they feel pain and understand death. (Or our best assessment of that — and moral reasoing often requires dealing with imperfect knowldedge).

The reason we don’t kill and eat our neighbor’s dog has nothing to do with killing. The dog is our neighbor’s property, and we wouldn’t kill it any more than we’d steal his car.

Those aren’t moral gymnastics, they’re simple precepts. Inflict minimal harm when you feed yourself. Don’t steal.

The trouble the Buddhists seem to have is that somebody else has decided for them that they shouldn’t kill animals, but they want to eat meat anyway.

I don’t entirely agree.

I don’t agree that we abstain from killing our neighbor’s dog just because it is our neighbor’s property – we attach more intrinsic value to animals that are friends of humans, even though they are biologically no different than wild animals. (Consider Americans’ utterly irrational revulsion toward eating horses. Consider the fact that if you hurt my cat, I would punch you, hard, not because I own my cat, but because I love her.)

And while I agree that most humans truly don’t believe plants feel pain, I think we, as a species, do a LOT of moral gymnastics about fish. The jury’s still out on their ability to feel pain, but the truth is that we have simply declared fish to be “other,” and by we, I mean almost all of humanity, down to the remaining hunter-gatherers.

I’m not saying all of this just to be contrary. I just think about it a lot, and I recognize that while I have chosen a path that is very aware and honest about my meat consumption, I am still prone to inconsistencies. I have to acknowledge that if I am at all interested in honesty.

Holly, I think you’re right just about down the line. Where we differ, I think, is simply in what we call “moral.” People certainly feel differently about animals we are accustomed to eating than we do about animals we keep as pets. But I think that’s a cultural, not a moral issue. Morally, killing my neighbor’s dog is exactly the same as killing my neighbor’s pig, cow, or lamb. My visceral feelings about dogs vs. lambs are very real, and come into play, but don’t affect the underlying moral issue.

I also think you’re right about people declaring fish to be “other,” (and I like the way you phrase it — it’s perfect), and that IS a moral issue about which people do those gymnastics. But I don’t think it takes a lot for a thoughtful hunter/gatherer to take a consistent stand on fish. The same rule — do minimal harm to feed yourself — can apply.

As for being contrary — let’s make a deal. Tovar, you’re in for this deal too, as are all your commenters. What makes these comment threads interesting is that we all see this a different way. Everyone’s thoughtful, everyone’s civil. If we all had to apologize for being contrary, I’d never have time to do anything else.

I can’t claim originatlity on the “other” line – I learned that from Mary Zeiss Stange’s Woman the Hunter.

As for the rest: Fair enough!

Thanks for the great exchange, Tamar and Holly!

Polite contrariness is a mighty fine habit to cultivate.

By the way, Tamar: I agree that we often do “moral gymnastics” in response to an imposed system of values, such as religious rules. But, as suggested in the post, I think we do something similar when — out of squeamishness or general discomfort with the idea of killing — we simply avoid thinking about where our food comes from.

Perhaps “moral sleight-of-hand” is a better phrase.

Nothing wrong with being inconsistent, Holly.

“A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds…”

Not quoting old Ralph Waldo to be funny or banal, but I think it’s equally appropriate in light of your comment here, Holly, and in the context of the Dalai Lama’s “moral gymnastics”. It makes no sense to mire ourselves in dogma at the expense of our own growth.

Or to throw another 19th Century voice into the mix, “Do I contradict myself? Very well then, I contradict myself. (I am large. I contain multitudes.)”

Because I believed something was true yesterday doesn’t mean I can’t believe it is false today. Our minds are capable of divergent thought, but we have to be willing to follow the paths they show us.

Today I would not kill and eat my neighbor’s dog. But tomorrow, with the world in collapse and my pantry bare… well, that could change. Or maybe I’ll eat my neighbor?

The concept of Other predates Ms. Strange by a century or two, but it’s also oddly relevant here because the things we designate Other (as opposed to Self) do not always have to be Other. If Self is a circle, and everything outside the circle is Other, then sometimes the circle may expand or contract. To the philosophical vegetarian (who eats no meat because he wishes to cause no harm), the circle may include cows and chickens. Over time, due to health, the circle may contract and begin to exclude eggs, milk, or cheese… or even beefsteaks.

All of this is, I think, perfectly natural by the way. It’s only our human nature and the odd obsession with self-examination and justification that makes it an issue.

More random thoughts, I suppose.

I probably would not eat my neighbors. They’d all require stewing.

I have a deep respect for Buddhism, but IMO this is a religious technicality that should evolve. In a world of factory farming, I believe it’s much more humane for a compassionate human to take responsibility for his/her meat than to rely on someone else who may not be so compassionate.

On a similar note, I once knew a guy who called me a murderer because I hunt. This is the same guy who took his kids to McDonald’s for burgers a couple times a week. His theory was basically that it’s modern livestock’s lot to be corralled and slaughtered on an assembly line. But to integrate a wild animal (that’s had the good fortune of living a free life) into our food system is murder. So livestock have no souls. I guess as long as the blood’s not on your hands, you’re sinless.

I’m with you, Eric, both in your respect for Buddhism and in your questioning of the technicality.

And, like you, I object to the split-view you describe: that cattle are just meat but deer are worthy beings. My feeling is that no animal is “just meat.” They are more than food; they have the capacity to suffer; they deserve respect. If we accept that, of course, we have to think more deeply about how we treat them: not a habit of mind encouraged at McDonald’s or Stop-n-Shop.

Yeah, I was just thinking about the Sabbath Goy tradition, a pragmatic workaround if ever there was one. I guess to me the distinction between ordering and buying is a bit artificial, because if you buy it then supply must increase to meet your added demand on the larger market. This is why I don’t buy factory farmed meat or unsustainable seafood; consumption is validation.

I don’t think there’s any doubt that we anthropomorphize certain species, privileging them over others; cute, fuzzy, and useful ones are pets, while pigs (every bit as smart, but not so cute, and also made of pork) are usually not. I think it’s safe to draw a line between mammals and fish, and having shucked some clams recently it’s hard to for me to ascribe sentience to shellfish. At the end of the day we all have our boundaries. What matters is that those boundaries are developed and informed over the course of serious thought and understanding about where different kinds of food come from. Having not eaten meat for 18 years, I feel that my return to carnivory is defensible because of the limits I place on it. And having recently killed and butchered a pig for the first time, I am OK with what meat means.

Hi, Peter, thanks for your comment. And welcome.

I really appreciate your thoughts on traditions and boundaries. So you’re another ex-vegetarian turned omnivore/carnivore, eh? There are a lot of us, it seems!